• Daily Life - Part II

Life in the Great Hall

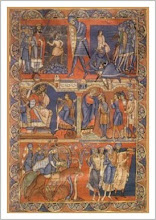

In the early medieval period the centre of life in castles was the Great Hall which was a huge multipurpose room built on the second floor. Medieval feasts, wedding celebrations, holiday festivities such as feast days, and receiving visiting nobles, would all take place in the castle's Great Hall. Elaborate tapestries and silks often lined the walls and while Middle Age castles could be rather dark, the largest windows would be found here. Small wooden or stone benches were often placed underneath these windows so guests could enjoy the view.

Great Hall furnishings could be sparse, but they were very practical. Long wooden tables and benches would be covered with white linen during feasts, but could be taken apart easily for dancing and entertainment. The lord and his family were seated at a table on a raised wooden or stone dais at the far end of the hall. There were no chimneys, and the fireplace was in the middle of the hall. Smoke escaped by the way of louvers in the roof, or at least in theory. It was not unusual for guests to sleep in the hall after a night of merrymaking.

The food at the lord's table was as full of variety as the peasant's was sparse. Meat, fish, pastries, cabbage, turnips, onions, carrots, beans, and peas were common, as well as fresh bread, stews, cheese and eggs, and fruit, desserts and tarts. At a feast spitted boar, roast swan, or peacock might be added. Beer, wine, cider, mead, juices and mulberry and blackberry wines were all drinks of choice in preference to water which was considered suspect and not as good for the digestion. Ale, which was thin, weak, and drunk soon after brewing, was the most common drink. Fruit juices and honey were the only sweeteners, and spices were almost unknown until after the Crusades. Meat was cut with small personal daggers and all eating was done with the fingers from trenchers, which were a flat, dry bread. One trencher and one drinking cup was shared by two people. Scraps were often thrown on the floor for the dogs to finish.

The stone floors in the castle's Great Hall were rarely covered with carpets. Straw and rushes were the usual coverings, but later in the Middle Ages herbs like marjoram, camomile, basil, sweet fennel, mint, germander and lavender would be added to help with the aroma. These coverings were swept regularly, but new materials would be soon added to cover up the more unattractive things which found their way onto the floor such as bones, spittle, spilt ale, dirt and grease.

The Roles of Seneschal, Marshal, and Constable:

The British scholar H.S. Bennett described the seneschal's role by saying that "the seneschal must know the size and needs of every manor; how many acres should be ploughed and how much seed will be needed. He must know all his bailiffs and reeves, how they conduct the lord's business and how they treat the peasants. He must know exactly how many penny loaves can be made from a quarter of corn, or how many cattle each pasture should support. He must for ever be on the alert lest any of the lord's franchises lapse or are usurped by others. He must think of the lord's needs, both of money and of kind, and see that they are constantly supplied. In short, he must be all knowing and he is all powerful". Steward is an alternative title for this role within a household.

In great households, the marshal was responsible for all aspects relating to horses: the care and management of all horses from the chargers to the pack horses, as well as all travel logistics. The position of marshal "horse servant" was a high one in court circles and the king's marshal was also responsible for managing many military matters. Within lower social groupings the marshal acted as a farrier. The highly skilled marshal made and fitted horseshoes, cared for the hoof, and provided general veterinary care for horses. Throughout the Middle Ages, a distinction was drawn between the marshal and the blacksmith.

The constable "count of the stable" was responsible for protection and the maintenance of order, and commanding the military component within the household. Along with marshals, the constable might also organise hastiludes and other chivalrous events.

On Horses, Riding, and Transportation:

Riding horses varied greatly in quality, size and breeding. The names of horses referred to a type of horse, rather than a breed. Many horses were described by the region where they or their immediate ancestors were foaled, by their gait eg. 'trotters' or 'amblers', or by their colouring or the name of their breeder.

The best riding horses were known as palfreys. Other riding horses were often called hackneys, from which the modern term "hack" is derived. Women sometimes rode palfreys or small quiet horses known as jennets.

Because of the necessity to ride long distances over uncertain roads, smooth gaited horses were preferred, and most ordinary riding horses were of greater value if they could do one of the smooth but ground covering four beat gaits collectively known as an amble rather than the more jarring trot.

It was common for many people including women to travel long distances, usually on horseback (or if weakened or infirm carried in a litter), and most early medieval women rode astride. The wives of nobles often accompanied their husbands on crusade or to tournaments, many women travelled for social or family engagements, and both nuns and laywomen went on pilgrimages. Women of the nobility also rode horses for sport, including when they were hunting and hawking.

It was not unheard of for women to also ride war horses and take part in warfare. For example, Empress Matilda, armed and mounted, led an army against her cousin King Stephen and his wife Matilda of Boulogne. (More to follow on the destrier, or war horse, in the Arms and Amour: Anglo-Norman Warfare section).

It was not uncommon for a girl to learn her father's trade or for a woman to share her husband's trade and many guilds also accepted the membership of widows so they might continue their husband's business. Under this system some women learnt horse related trades and there are records of women working as farriers and saddle makers. On farms where every hand was needed, excessive emphasis on division of labour wasn't practical. Women often worked alongside men on their own farms or as hired help, leading the farm horses and oxen and managing their care.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment