This section of the blog consists of:

• Daily Life - 3 parts

• Fun Stuff ~ Quizzes

• Image Gallery - which can now be found *Here*

• Fun Stuff ~ Quizzes

To conclude this section of the blog I've decided to post a couple of quick quizzes for readers to play around with before I get back into the more serious stuff such as Anglo-Norman Warfare, the Biographies, and an indepth look at the reign of King Stephen. Enjoy!

Quiz No. 1

Test your knowledge of the late Saxon/Norman period:

1. Alfred the Great reigned from:

a. 791-820

b. 871-900

c. 659-679

2. Along with feudalism, the Normans bought to Britain a particular style of architecture best described as:

a. Early English Gothic - flying buttresses

b. Concentric castle building - curtain walls and barbicans

c. Romanesque - chevron and beakhead ornamentation

3. Edward the Confessor founded Westminster Abbey in:

a. 1042

b. 1141

c. 1045

4. The compilation of the 'Doomsday Book' took place in:

a. 1086

b. 1082

c. 1126

5. Who ruled the House of Wessex in the years between 940-946:

a. Edgar

b. Edmund I

c. Ethelred II

Quiz No. 2

The House of Normandy:

1. Duke William of Normandy was also known as:

a. The Bastard

b. Curtmantle

c. Longshanks

2. His son was known as William Rufus because:

a. he often wore a red cloak

b. of his ruddy complexion

c. he liked to hunt red deer in Nottingham Forest

3. King Stephen, the last of the Norman Kings, ruled England during the years:

a. 1035-54

b. 1135-54

c. 1126-54

4. Geoffrey of Anjou, husband of The Empress Matilda, founded the Plantagenet family name when he chose the planta genista as his emblem - this was:

a. a sprig of yellow broom flower

b. a sprig from a young oak tree

c. a sprig of heather

5. Henry II ruled England between:

a. 1054-89

b. 1154-89

c. 1135-89

Quiz No. 3

The Saxon and Norman era:

1. A 'Who am I?' question. It has been said my marriage got off to a somewhat stormy, violent start but it proved sound and 11 children were produced from it. I died in 1083 and was buried at l'Abbaye aux Dames which I had founded.

a. Eleanor of Aquitane

b. Matilda of Flanders

c. Margaret of Anjou

2. Many fine words have been spoken of this member of the House of Wessex who ruled during the years 871AD-900AD.

a. Athelstan

b. Edward, the Martyr

c. Alfred, the Great

3. This former Queen wed William d'Aubigny in 1139, and unlike her previous marriage which failed to produce any children, this second marriage produced 7 children who survived until adulthood.

a. Matilda of Boulogne

b. Adelica of Louvain (Adeliza of Leuven)

c. Adela, Countess of Blois

4. This man was the mainstay of The Empress Matilda's campaigns to wrest the English crown from Stephen of Blois.

a. Robert of Gloucester

b. William of Anjou

c. Robert of Leicester

5. History often applies the moniker of 'The Unready' to this sovereign's name.

a. Edmund I

b. Egbert

c. Ethelred II

Now of course you didn't cheat LOL! Here are the answers:

Showing posts with label the anarchy - life in medieval England: Daily Life. Show all posts

Showing posts with label the anarchy - life in medieval England: Daily Life. Show all posts

02 July 2010

Life in Medieval England

• Daily Life - Part III

General Information

The Often Thorny Subject of Marriage and Dowry:

Anglo-Saxon marriage customs allowed that not only did women have rights covered in legislation, and were able to own property and lands, but that the husband was to pay "morgengifu" ('morning gift') in money or land to the woman herself, and she would have personal control over it to give away, sell or bequeath as she chose.

This of course all changed after the advent of the Norman Conquest in 1066, bringing with it the customs and laws of the Normans, and indeed there was great change in the rights and status of women. For those of high ranking birth especially, marriage was most often arranged by the woman's family or by the powerful, sometimes by the monarch himself, purely for political or personal gain, or in some cases as a reward to a favourite or for loyal services rendered. Women had a very limited share in feudal land owning, the husband owned everything, and Canon Law stated that no married woman could make a valid will without her husband's consent. Children were married at a young age, with the age of valid consent for girls being 12 years. Some young daughters were placed in an abbey and 'took the veil'. It was also fairly common for women to become nuns after the death of their husband. The only women with relative freedom to do what they wanted were rich widows. Some noble women were named heir to titles and estates, but it was still expected that a marriage would take place even for these women.

In fairness though, it would seem that this arrangement was sometimes just as distasteful to the husband, especially if he had no regard for the chosen woman.

Church and Daily Life:

Church and daily life were very closely tied together, and even the King was expected to attend chapel services. Indeed many Norman Keeps had a chapel, the best example of which is St John the Evangelist in White Tower, London.

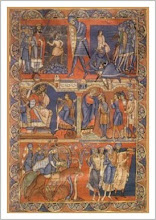

A Book of Hours, an illuminated book of prayers, texts, and psalms become the one of most common type of medieval illuminated manuscript. Some ladies of high ranking households also had a prie-dieu in their living quarters or solar. A prie-dieu (French: literally, "pray God") is a type of prayer desk mainly intended for private devotional use, but they can also often be found in churches of the European continent. It is a small ornamental wooden desk furnished with a sloping shelf for books, and a cushioned pad on which to kneel. Sometimes a prie-dieu consisted only of the sloped shelf for books without the kneeler, or instead of the sloping shelf a padded arm rest was provided.

Medieval Literature:

The Middle Ages saw the beginnings of a rebirth in literature. Early medieval books were painstakingly hand copied and illustrated by monks. Paper was a rarity, with vellum, made from calf's skin, and parchment, made from lamb's skin, were the media of choice for writing. Students learning to write used wooden tablets covered in green or black wax. Most books during this era were bound with plain wooden boards, or with simple tooled leather for more expensive volumes.

Language also saw further development during the Middle Ages. Capital and lowercase letters were developed with rules for each. Books were treasures and were rarely shown openly in a library, but rather kept safely under lock and key. Indeed, some people might have been tempted to rent out their books, while for others desperate for cash a book was a valuable item that could be pawned.

In addition, wandering scholars and poets travelling to the Crusades learned of new writing styles. Courtly Love spawned interest in romantic prose. Troubadours sang in medieval courtyards about epic battles involving Roland, Arthur, and Charlemagne.

Some Literary Works:

Anthology of Old English Poetry:

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis, which dates to the tenth century, is an anthology of Anglo-Saxon poetry, and one of the four major Anglo-Saxon literature codices. It was donated to the library of Exeter Cathedral by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, and is the largest known collection of Old English literature that exists today. Proposed dates of authorship range from 960AD to 990AD. However, the Book's heritage becomes traceable around 1050 when Leofric was made Bishop at Exeter. Among the treasures which he is recorded to have bestowed upon the then impoverished monastery is one described as "mycel englisc boc be gehwilcum þingum on leoðwisan geworht" - that is: "a large English book of poetic works". This book has been widely assumed to be the Exeter Codex as it survives today.

A Link which includes further information and images of the text:

• The Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry

Romance Genre and the Song of Roland:

As a literary genre, romance or chivalric romance refers to a style of heroic prose and verse narrative current in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Romances often drew on the legends and fairy tales and traditional tales about Charlemagne and Roland or King Arthur.

The Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland) is the oldest remaining major work of French literature. It exists in various different manuscript versions, which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. The oldest of these versions is the one in the Oxford manuscript, which contains a text of some 4,004 lines (the number varies slightly in different modern editions) and is usually dated to the middle of the twelfth century, ie. between 1140 and 1170. The epic poem is the first and most outstanding example of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries and celebrated the legendary deeds of a hero.

• The Song of Roland

The Lais of Marie de France:

These are a series of twelve short narrative Breton lais written by the poet Marie de France in the late twelfth century. They are short, narrative poems that are notable for their celebration of love and in general focus on glorifying the concept of courtly love through the adventures of their main characters. Two of Marie's lais "Lanval" and "Chevrefoil" mention King Arthur and his Knights. Very little is known about Marie herself but it is thought she was born in France and wrote in England and was probably a contemporary of Chrétien de Troyes.

Harley 978, a thirteenth century manuscript housed in the British Library, preserves all twelve lais. The manuscript also includes a 56 line prologue in which Marie writes that she was inspired by the example of the ancient Greeks and Romans to create something that would be both entertaining and morally instructive, and she also states her desire to preserve for posterity the tales that she has heard.

• The Lais of Marie de France

Medieval Clothing and Jewellery:

The following links provide some very interesting information and images about medieval jewellery and clothing. They include information about the materials used, styles, and the social and economic value of jewellery items, as well as the garments worn by both men and women.

• Medieval Jewelry and Clothing.

• "Wool is the whole wealth of my people"

• Fashion - Saxon and Medieval

• Hullwebs - daily life, marriage, and family

• Anglo-Saxon Women 410AD to 1066

For women in particular, spinning and weaving, needlework and tapestry, and the preparation of 'Simples', homemade herbal remedies for various ailments, were common pursuits.

General Information

The Often Thorny Subject of Marriage and Dowry:

Anglo-Saxon marriage customs allowed that not only did women have rights covered in legislation, and were able to own property and lands, but that the husband was to pay "morgengifu" ('morning gift') in money or land to the woman herself, and she would have personal control over it to give away, sell or bequeath as she chose.

This of course all changed after the advent of the Norman Conquest in 1066, bringing with it the customs and laws of the Normans, and indeed there was great change in the rights and status of women. For those of high ranking birth especially, marriage was most often arranged by the woman's family or by the powerful, sometimes by the monarch himself, purely for political or personal gain, or in some cases as a reward to a favourite or for loyal services rendered. Women had a very limited share in feudal land owning, the husband owned everything, and Canon Law stated that no married woman could make a valid will without her husband's consent. Children were married at a young age, with the age of valid consent for girls being 12 years. Some young daughters were placed in an abbey and 'took the veil'. It was also fairly common for women to become nuns after the death of their husband. The only women with relative freedom to do what they wanted were rich widows. Some noble women were named heir to titles and estates, but it was still expected that a marriage would take place even for these women.

In fairness though, it would seem that this arrangement was sometimes just as distasteful to the husband, especially if he had no regard for the chosen woman.

Church and Daily Life:

Church and daily life were very closely tied together, and even the King was expected to attend chapel services. Indeed many Norman Keeps had a chapel, the best example of which is St John the Evangelist in White Tower, London.

A Book of Hours, an illuminated book of prayers, texts, and psalms become the one of most common type of medieval illuminated manuscript. Some ladies of high ranking households also had a prie-dieu in their living quarters or solar. A prie-dieu (French: literally, "pray God") is a type of prayer desk mainly intended for private devotional use, but they can also often be found in churches of the European continent. It is a small ornamental wooden desk furnished with a sloping shelf for books, and a cushioned pad on which to kneel. Sometimes a prie-dieu consisted only of the sloped shelf for books without the kneeler, or instead of the sloping shelf a padded arm rest was provided.

Medieval Literature:

The Middle Ages saw the beginnings of a rebirth in literature. Early medieval books were painstakingly hand copied and illustrated by monks. Paper was a rarity, with vellum, made from calf's skin, and parchment, made from lamb's skin, were the media of choice for writing. Students learning to write used wooden tablets covered in green or black wax. Most books during this era were bound with plain wooden boards, or with simple tooled leather for more expensive volumes.

Language also saw further development during the Middle Ages. Capital and lowercase letters were developed with rules for each. Books were treasures and were rarely shown openly in a library, but rather kept safely under lock and key. Indeed, some people might have been tempted to rent out their books, while for others desperate for cash a book was a valuable item that could be pawned.

In addition, wandering scholars and poets travelling to the Crusades learned of new writing styles. Courtly Love spawned interest in romantic prose. Troubadours sang in medieval courtyards about epic battles involving Roland, Arthur, and Charlemagne.

Some Literary Works:

Anthology of Old English Poetry:

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis, which dates to the tenth century, is an anthology of Anglo-Saxon poetry, and one of the four major Anglo-Saxon literature codices. It was donated to the library of Exeter Cathedral by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, and is the largest known collection of Old English literature that exists today. Proposed dates of authorship range from 960AD to 990AD. However, the Book's heritage becomes traceable around 1050 when Leofric was made Bishop at Exeter. Among the treasures which he is recorded to have bestowed upon the then impoverished monastery is one described as "mycel englisc boc be gehwilcum þingum on leoðwisan geworht" - that is: "a large English book of poetic works". This book has been widely assumed to be the Exeter Codex as it survives today.

A Link which includes further information and images of the text:

• The Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry

Romance Genre and the Song of Roland:

As a literary genre, romance or chivalric romance refers to a style of heroic prose and verse narrative current in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Romances often drew on the legends and fairy tales and traditional tales about Charlemagne and Roland or King Arthur.

The Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland) is the oldest remaining major work of French literature. It exists in various different manuscript versions, which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. The oldest of these versions is the one in the Oxford manuscript, which contains a text of some 4,004 lines (the number varies slightly in different modern editions) and is usually dated to the middle of the twelfth century, ie. between 1140 and 1170. The epic poem is the first and most outstanding example of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries and celebrated the legendary deeds of a hero.

• The Song of Roland

The Lais of Marie de France:

These are a series of twelve short narrative Breton lais written by the poet Marie de France in the late twelfth century. They are short, narrative poems that are notable for their celebration of love and in general focus on glorifying the concept of courtly love through the adventures of their main characters. Two of Marie's lais "Lanval" and "Chevrefoil" mention King Arthur and his Knights. Very little is known about Marie herself but it is thought she was born in France and wrote in England and was probably a contemporary of Chrétien de Troyes.

Harley 978, a thirteenth century manuscript housed in the British Library, preserves all twelve lais. The manuscript also includes a 56 line prologue in which Marie writes that she was inspired by the example of the ancient Greeks and Romans to create something that would be both entertaining and morally instructive, and she also states her desire to preserve for posterity the tales that she has heard.

• The Lais of Marie de France

Medieval Clothing and Jewellery:

The following links provide some very interesting information and images about medieval jewellery and clothing. They include information about the materials used, styles, and the social and economic value of jewellery items, as well as the garments worn by both men and women.

• Medieval Jewelry and Clothing.

• "Wool is the whole wealth of my people"

• Fashion - Saxon and Medieval

• Hullwebs - daily life, marriage, and family

• Anglo-Saxon Women 410AD to 1066

For women in particular, spinning and weaving, needlework and tapestry, and the preparation of 'Simples', homemade herbal remedies for various ailments, were common pursuits.

01 July 2010

Life in Medieval England

• Daily Life - Part II

Life in the Great Hall

In the early medieval period the centre of life in castles was the Great Hall which was a huge multipurpose room built on the second floor. Medieval feasts, wedding celebrations, holiday festivities such as feast days, and receiving visiting nobles, would all take place in the castle's Great Hall. Elaborate tapestries and silks often lined the walls and while Middle Age castles could be rather dark, the largest windows would be found here. Small wooden or stone benches were often placed underneath these windows so guests could enjoy the view.

Great Hall furnishings could be sparse, but they were very practical. Long wooden tables and benches would be covered with white linen during feasts, but could be taken apart easily for dancing and entertainment. The lord and his family were seated at a table on a raised wooden or stone dais at the far end of the hall. There were no chimneys, and the fireplace was in the middle of the hall. Smoke escaped by the way of louvers in the roof, or at least in theory. It was not unusual for guests to sleep in the hall after a night of merrymaking.

The food at the lord's table was as full of variety as the peasant's was sparse. Meat, fish, pastries, cabbage, turnips, onions, carrots, beans, and peas were common, as well as fresh bread, stews, cheese and eggs, and fruit, desserts and tarts. At a feast spitted boar, roast swan, or peacock might be added. Beer, wine, cider, mead, juices and mulberry and blackberry wines were all drinks of choice in preference to water which was considered suspect and not as good for the digestion. Ale, which was thin, weak, and drunk soon after brewing, was the most common drink. Fruit juices and honey were the only sweeteners, and spices were almost unknown until after the Crusades. Meat was cut with small personal daggers and all eating was done with the fingers from trenchers, which were a flat, dry bread. One trencher and one drinking cup was shared by two people. Scraps were often thrown on the floor for the dogs to finish.

The stone floors in the castle's Great Hall were rarely covered with carpets. Straw and rushes were the usual coverings, but later in the Middle Ages herbs like marjoram, camomile, basil, sweet fennel, mint, germander and lavender would be added to help with the aroma. These coverings were swept regularly, but new materials would be soon added to cover up the more unattractive things which found their way onto the floor such as bones, spittle, spilt ale, dirt and grease.

The Roles of Seneschal, Marshal, and Constable:

The British scholar H.S. Bennett described the seneschal's role by saying that "the seneschal must know the size and needs of every manor; how many acres should be ploughed and how much seed will be needed. He must know all his bailiffs and reeves, how they conduct the lord's business and how they treat the peasants. He must know exactly how many penny loaves can be made from a quarter of corn, or how many cattle each pasture should support. He must for ever be on the alert lest any of the lord's franchises lapse or are usurped by others. He must think of the lord's needs, both of money and of kind, and see that they are constantly supplied. In short, he must be all knowing and he is all powerful". Steward is an alternative title for this role within a household.

In great households, the marshal was responsible for all aspects relating to horses: the care and management of all horses from the chargers to the pack horses, as well as all travel logistics. The position of marshal "horse servant" was a high one in court circles and the king's marshal was also responsible for managing many military matters. Within lower social groupings the marshal acted as a farrier. The highly skilled marshal made and fitted horseshoes, cared for the hoof, and provided general veterinary care for horses. Throughout the Middle Ages, a distinction was drawn between the marshal and the blacksmith.

The constable "count of the stable" was responsible for protection and the maintenance of order, and commanding the military component within the household. Along with marshals, the constable might also organise hastiludes and other chivalrous events.

On Horses, Riding, and Transportation:

Riding horses varied greatly in quality, size and breeding. The names of horses referred to a type of horse, rather than a breed. Many horses were described by the region where they or their immediate ancestors were foaled, by their gait eg. 'trotters' or 'amblers', or by their colouring or the name of their breeder.

The best riding horses were known as palfreys. Other riding horses were often called hackneys, from which the modern term "hack" is derived. Women sometimes rode palfreys or small quiet horses known as jennets.

Because of the necessity to ride long distances over uncertain roads, smooth gaited horses were preferred, and most ordinary riding horses were of greater value if they could do one of the smooth but ground covering four beat gaits collectively known as an amble rather than the more jarring trot.

It was common for many people including women to travel long distances, usually on horseback (or if weakened or infirm carried in a litter), and most early medieval women rode astride. The wives of nobles often accompanied their husbands on crusade or to tournaments, many women travelled for social or family engagements, and both nuns and laywomen went on pilgrimages. Women of the nobility also rode horses for sport, including when they were hunting and hawking.

It was not unheard of for women to also ride war horses and take part in warfare. For example, Empress Matilda, armed and mounted, led an army against her cousin King Stephen and his wife Matilda of Boulogne. (More to follow on the destrier, or war horse, in the Arms and Amour: Anglo-Norman Warfare section).

It was not uncommon for a girl to learn her father's trade or for a woman to share her husband's trade and many guilds also accepted the membership of widows so they might continue their husband's business. Under this system some women learnt horse related trades and there are records of women working as farriers and saddle makers. On farms where every hand was needed, excessive emphasis on division of labour wasn't practical. Women often worked alongside men on their own farms or as hired help, leading the farm horses and oxen and managing their care.

Life in the Great Hall

In the early medieval period the centre of life in castles was the Great Hall which was a huge multipurpose room built on the second floor. Medieval feasts, wedding celebrations, holiday festivities such as feast days, and receiving visiting nobles, would all take place in the castle's Great Hall. Elaborate tapestries and silks often lined the walls and while Middle Age castles could be rather dark, the largest windows would be found here. Small wooden or stone benches were often placed underneath these windows so guests could enjoy the view.

Great Hall furnishings could be sparse, but they were very practical. Long wooden tables and benches would be covered with white linen during feasts, but could be taken apart easily for dancing and entertainment. The lord and his family were seated at a table on a raised wooden or stone dais at the far end of the hall. There were no chimneys, and the fireplace was in the middle of the hall. Smoke escaped by the way of louvers in the roof, or at least in theory. It was not unusual for guests to sleep in the hall after a night of merrymaking.

The food at the lord's table was as full of variety as the peasant's was sparse. Meat, fish, pastries, cabbage, turnips, onions, carrots, beans, and peas were common, as well as fresh bread, stews, cheese and eggs, and fruit, desserts and tarts. At a feast spitted boar, roast swan, or peacock might be added. Beer, wine, cider, mead, juices and mulberry and blackberry wines were all drinks of choice in preference to water which was considered suspect and not as good for the digestion. Ale, which was thin, weak, and drunk soon after brewing, was the most common drink. Fruit juices and honey were the only sweeteners, and spices were almost unknown until after the Crusades. Meat was cut with small personal daggers and all eating was done with the fingers from trenchers, which were a flat, dry bread. One trencher and one drinking cup was shared by two people. Scraps were often thrown on the floor for the dogs to finish.

The stone floors in the castle's Great Hall were rarely covered with carpets. Straw and rushes were the usual coverings, but later in the Middle Ages herbs like marjoram, camomile, basil, sweet fennel, mint, germander and lavender would be added to help with the aroma. These coverings were swept regularly, but new materials would be soon added to cover up the more unattractive things which found their way onto the floor such as bones, spittle, spilt ale, dirt and grease.

The Roles of Seneschal, Marshal, and Constable:

The British scholar H.S. Bennett described the seneschal's role by saying that "the seneschal must know the size and needs of every manor; how many acres should be ploughed and how much seed will be needed. He must know all his bailiffs and reeves, how they conduct the lord's business and how they treat the peasants. He must know exactly how many penny loaves can be made from a quarter of corn, or how many cattle each pasture should support. He must for ever be on the alert lest any of the lord's franchises lapse or are usurped by others. He must think of the lord's needs, both of money and of kind, and see that they are constantly supplied. In short, he must be all knowing and he is all powerful". Steward is an alternative title for this role within a household.

In great households, the marshal was responsible for all aspects relating to horses: the care and management of all horses from the chargers to the pack horses, as well as all travel logistics. The position of marshal "horse servant" was a high one in court circles and the king's marshal was also responsible for managing many military matters. Within lower social groupings the marshal acted as a farrier. The highly skilled marshal made and fitted horseshoes, cared for the hoof, and provided general veterinary care for horses. Throughout the Middle Ages, a distinction was drawn between the marshal and the blacksmith.

The constable "count of the stable" was responsible for protection and the maintenance of order, and commanding the military component within the household. Along with marshals, the constable might also organise hastiludes and other chivalrous events.

On Horses, Riding, and Transportation:

Riding horses varied greatly in quality, size and breeding. The names of horses referred to a type of horse, rather than a breed. Many horses were described by the region where they or their immediate ancestors were foaled, by their gait eg. 'trotters' or 'amblers', or by their colouring or the name of their breeder.

The best riding horses were known as palfreys. Other riding horses were often called hackneys, from which the modern term "hack" is derived. Women sometimes rode palfreys or small quiet horses known as jennets.

Because of the necessity to ride long distances over uncertain roads, smooth gaited horses were preferred, and most ordinary riding horses were of greater value if they could do one of the smooth but ground covering four beat gaits collectively known as an amble rather than the more jarring trot.

It was common for many people including women to travel long distances, usually on horseback (or if weakened or infirm carried in a litter), and most early medieval women rode astride. The wives of nobles often accompanied their husbands on crusade or to tournaments, many women travelled for social or family engagements, and both nuns and laywomen went on pilgrimages. Women of the nobility also rode horses for sport, including when they were hunting and hawking.

It was not unheard of for women to also ride war horses and take part in warfare. For example, Empress Matilda, armed and mounted, led an army against her cousin King Stephen and his wife Matilda of Boulogne. (More to follow on the destrier, or war horse, in the Arms and Amour: Anglo-Norman Warfare section).

It was not uncommon for a girl to learn her father's trade or for a woman to share her husband's trade and many guilds also accepted the membership of widows so they might continue their husband's business. Under this system some women learnt horse related trades and there are records of women working as farriers and saddle makers. On farms where every hand was needed, excessive emphasis on division of labour wasn't practical. Women often worked alongside men on their own farms or as hired help, leading the farm horses and oxen and managing their care.

Life in Medieval England

• Daily Life - Part I

Feudalism and Medieval life

Feudalism: What does feudalism and all that it entails mean? Find out here

The social structure of the Middle Ages was organised around the system of Feudalism. In practice it meant that a country was not governed solely by the king but by individual barons, who administered their own estates, dispensed their own justice, minted their own money, levied taxes and tolls, and demanded military service from vassals. Sometimes the barons could field greater armies than the king. In theory the king was the chief feudal lord, but in reality the many individual barons were supreme in their own territory.

Feudalism was built upon a relationship of obligation and mutual service between vassals and lords. A vassal held his land, or fief, as a grant from a lord. When a vassal died, his heir was required to publicly renew his oath of fealty to his lord or suzerain. This public oath was called homage. The lord was obliged to protect the vassal, give military aid, and guard his children. If a daughter inherited, the lord arranged her marriage. If there were no heirs the lord disposed of the fief as he chose. A vassal was required to attend the lord at his court, help administer justice, and contribute money if needed. He was required to answer a summons to battle and bring an agreed upon number of fighting men. In addition he was obligated to feed and house the lord and his company when they travelled across his land.

What was life like for ordinary people under this system?

Manors rather than villages were the economic and social units of life in the early Medieval period. A manor consisted of a manor house, one or more villages, and up to several thousand acres of land divided into meadow, pasture, forest, and cultivated fields. The fields were further divided into strips - 1/3 for the lord of the manor, less for the church, and the remainder for the peasants and serfs. At least half of the working days were spent tending the land belonging to the lord and the church. Some time was also spent doing maintenance and on special tasks such as clearing land, cutting firewood, and building roads and bridges. The rest of the time the villagers were free to work their own land. A serf was bound to a lord for life and needed the lord's permission to marry. They couldn't own property or leave the land without the lord's permission. However, in theory at least a serf couldn't be displaced if the manor changed hands, nor be forced to fight, and he was entitled to the protection of the lord. Most families lived in rough huts with dirt floors and no chimneys or windows. One end of the hut was often given over to livestock. Furnishings were sparse and often consisted of little more than stools, a trestle table, and beds on the floor softened with straw or leaves. Their diet was plain and included porridge, cheese, bread, and a few home grown vegetables. Life was hard but people didn't work on Sundays or Saints Days, and they could go to nearby fairs and markets. Generally speaking, daily life was aligned very closely to the seasons eg. sowing and planting time, the harvest etc.

• Notes About Medieval Celebrations:

Medieval celebrations revolved around feast days that had pagan origins and were based on ancient agricultural celebrations that marked when certain crops should be planted or harvested. They also relate to the development of the Christian Church. Below is a short list of feast days and celebrations in the yearly cycle.

* Michaelmas, 29th September - Michaelmas marked the beginning of winter and the start of the fiscal year for tradesmen. Wheat and rye were sown from Michaelmas to Christmas.

* By November, feed was often too scarce to keep animals through the winter, and became known as the "blood month" when meat was smoked, salted and cured for consumption during the long winter ahead. The month began with All Hallows (All Saints) Day, followed by St Martin's Day on 11th November.

* Winter Solstice, 21-23rd December: shortest day of the year, longest night, preparing the soil for Spring.

* Christmas or Yule: The two week period from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day on 6th January became the longest vacation for workers. The Lord of the manor or castle often gave bonuses of food, clothing, drink and firewood to servants. Houses were decked with holly and ivy, and giant Yule logs were brought in and burned throughout the celebration. New Year's took place during this time and added to the festivities, and "First Gifts" were often exchanged on this day.

* Spring crops would be planted from the end of Christmas through Easter.

* Twelfth Night, 5th January: the end of Christmas festivities and to honour abundance and fertility for the year.

* "Plow Monday" took place the day after Epiphany, and freemen of the village would participate in a plough race to begin cultivation of the town's common plot of land. Each man would try and furrow as many lines as possible because he would be able to sow those lines during the coming year.

* Candlemas, 2nd February: the eve of Candlemas was the day on which Christmas decorations of greenery were removed from people's homes.

* Easter was another day for exchanging gifts. The castle lord would receive eggs from the villagers and in return provide servants with dinner. A lesser celebration was Hocktide, the end of the Easter week. In medieval Britain there was an egg throwing festival held in the churches at Easter. The priest would give out one hard boiled egg which was tossed around the nave of the church and the choirboy who was holding the egg when the clock struck twelve would get to keep it.

* Spring Equinox, March: beginnings and new life

* May Day: marks the end of the winter half of the year, celebrates the spring planting season. May Day, the Rogation Days, Ascension saw celebrations of love, especially on the 1st. Villagers would venture into the woods to cut wildflowers and other greenery for their homes to usher in May and hope for a fertile season.

* Pentecost, or Whitsunday: celebrated 7 weeks after Easter Sunday with a feast of the Church.

* Summer Solstice, 21-23rd June: St. John's Day 24th June, Midsummer bonfires, garlands, longest day of the year and shortest night.

* Lammas, or Feast of St Peter, 1st August: Lammas Day (loaf-mass day), the festival of the first wheat harvest of the year. On this day it was customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop. In many parts of England, tenants were bound to present freshly harvested wheat to their landlords on or before the first day of August. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where it is referred to regularly, it is called "the feast of first fruits".

* Autumn Equinox, September: end of summer and the harvest

• Notes about Medieval Market Towns and Inns:

The term 'market town' is a legal term that originated during the medieval period meaning a settlement that has the right to host markets. This distinguishes a town from a village or city. Market towns were frequently located where there was ready access to transport eg. at a crossroads or close to a river ford and near castles which offered protection. As market towns developed a system was devised whereby a new market town could not be established within a certain travelling distance, usually within one days travel to and from the market, of an existing one.

Traditional market towns usually had a wide main street or central market square which provided room for traders to set up stalls and booths on market days. Sometimes a market cross was erected in the centre of town both to obtain a blessing on the trade conducted and eventually market halls were developed which included administrative quarters on the first floor above the covered market.

Medieval Inns were usually located along main roads and traditionally provided not only food, drinks, and lodgings but also stabling and fodder for a traveller's horse. Inns also acted as community gathering places and, especially in rural areas, provided a place for people to meet, socialise and exchange news.

"Whosoever shall brew ale in the town with intention of selling it must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale."

Feudalism and Medieval life

Feudalism: What does feudalism and all that it entails mean? Find out here

The social structure of the Middle Ages was organised around the system of Feudalism. In practice it meant that a country was not governed solely by the king but by individual barons, who administered their own estates, dispensed their own justice, minted their own money, levied taxes and tolls, and demanded military service from vassals. Sometimes the barons could field greater armies than the king. In theory the king was the chief feudal lord, but in reality the many individual barons were supreme in their own territory.

Feudalism was built upon a relationship of obligation and mutual service between vassals and lords. A vassal held his land, or fief, as a grant from a lord. When a vassal died, his heir was required to publicly renew his oath of fealty to his lord or suzerain. This public oath was called homage. The lord was obliged to protect the vassal, give military aid, and guard his children. If a daughter inherited, the lord arranged her marriage. If there were no heirs the lord disposed of the fief as he chose. A vassal was required to attend the lord at his court, help administer justice, and contribute money if needed. He was required to answer a summons to battle and bring an agreed upon number of fighting men. In addition he was obligated to feed and house the lord and his company when they travelled across his land.

What was life like for ordinary people under this system?

Manors rather than villages were the economic and social units of life in the early Medieval period. A manor consisted of a manor house, one or more villages, and up to several thousand acres of land divided into meadow, pasture, forest, and cultivated fields. The fields were further divided into strips - 1/3 for the lord of the manor, less for the church, and the remainder for the peasants and serfs. At least half of the working days were spent tending the land belonging to the lord and the church. Some time was also spent doing maintenance and on special tasks such as clearing land, cutting firewood, and building roads and bridges. The rest of the time the villagers were free to work their own land. A serf was bound to a lord for life and needed the lord's permission to marry. They couldn't own property or leave the land without the lord's permission. However, in theory at least a serf couldn't be displaced if the manor changed hands, nor be forced to fight, and he was entitled to the protection of the lord. Most families lived in rough huts with dirt floors and no chimneys or windows. One end of the hut was often given over to livestock. Furnishings were sparse and often consisted of little more than stools, a trestle table, and beds on the floor softened with straw or leaves. Their diet was plain and included porridge, cheese, bread, and a few home grown vegetables. Life was hard but people didn't work on Sundays or Saints Days, and they could go to nearby fairs and markets. Generally speaking, daily life was aligned very closely to the seasons eg. sowing and planting time, the harvest etc.

• Notes About Medieval Celebrations:

Medieval celebrations revolved around feast days that had pagan origins and were based on ancient agricultural celebrations that marked when certain crops should be planted or harvested. They also relate to the development of the Christian Church. Below is a short list of feast days and celebrations in the yearly cycle.

* Michaelmas, 29th September - Michaelmas marked the beginning of winter and the start of the fiscal year for tradesmen. Wheat and rye were sown from Michaelmas to Christmas.

* By November, feed was often too scarce to keep animals through the winter, and became known as the "blood month" when meat was smoked, salted and cured for consumption during the long winter ahead. The month began with All Hallows (All Saints) Day, followed by St Martin's Day on 11th November.

* Winter Solstice, 21-23rd December: shortest day of the year, longest night, preparing the soil for Spring.

* Christmas or Yule: The two week period from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day on 6th January became the longest vacation for workers. The Lord of the manor or castle often gave bonuses of food, clothing, drink and firewood to servants. Houses were decked with holly and ivy, and giant Yule logs were brought in and burned throughout the celebration. New Year's took place during this time and added to the festivities, and "First Gifts" were often exchanged on this day.

* Spring crops would be planted from the end of Christmas through Easter.

* Twelfth Night, 5th January: the end of Christmas festivities and to honour abundance and fertility for the year.

* "Plow Monday" took place the day after Epiphany, and freemen of the village would participate in a plough race to begin cultivation of the town's common plot of land. Each man would try and furrow as many lines as possible because he would be able to sow those lines during the coming year.

* Candlemas, 2nd February: the eve of Candlemas was the day on which Christmas decorations of greenery were removed from people's homes.

* Easter was another day for exchanging gifts. The castle lord would receive eggs from the villagers and in return provide servants with dinner. A lesser celebration was Hocktide, the end of the Easter week. In medieval Britain there was an egg throwing festival held in the churches at Easter. The priest would give out one hard boiled egg which was tossed around the nave of the church and the choirboy who was holding the egg when the clock struck twelve would get to keep it.

* Spring Equinox, March: beginnings and new life

* May Day: marks the end of the winter half of the year, celebrates the spring planting season. May Day, the Rogation Days, Ascension saw celebrations of love, especially on the 1st. Villagers would venture into the woods to cut wildflowers and other greenery for their homes to usher in May and hope for a fertile season.

* Pentecost, or Whitsunday: celebrated 7 weeks after Easter Sunday with a feast of the Church.

* Summer Solstice, 21-23rd June: St. John's Day 24th June, Midsummer bonfires, garlands, longest day of the year and shortest night.

* Lammas, or Feast of St Peter, 1st August: Lammas Day (loaf-mass day), the festival of the first wheat harvest of the year. On this day it was customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop. In many parts of England, tenants were bound to present freshly harvested wheat to their landlords on or before the first day of August. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where it is referred to regularly, it is called "the feast of first fruits".

* Autumn Equinox, September: end of summer and the harvest

• Notes about Medieval Market Towns and Inns:

The term 'market town' is a legal term that originated during the medieval period meaning a settlement that has the right to host markets. This distinguishes a town from a village or city. Market towns were frequently located where there was ready access to transport eg. at a crossroads or close to a river ford and near castles which offered protection. As market towns developed a system was devised whereby a new market town could not be established within a certain travelling distance, usually within one days travel to and from the market, of an existing one.

Traditional market towns usually had a wide main street or central market square which provided room for traders to set up stalls and booths on market days. Sometimes a market cross was erected in the centre of town both to obtain a blessing on the trade conducted and eventually market halls were developed which included administrative quarters on the first floor above the covered market.

Medieval Inns were usually located along main roads and traditionally provided not only food, drinks, and lodgings but also stabling and fodder for a traveller's horse. Inns also acted as community gathering places and, especially in rural areas, provided a place for people to meet, socialise and exchange news.

"Whosoever shall brew ale in the town with intention of selling it must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)