• Daily Life - Part III

General Information

The Often Thorny Subject of Marriage and Dowry:

Anglo-Saxon marriage customs allowed that not only did women have rights covered in legislation, and were able to own property and lands, but that the husband was to pay "morgengifu" ('morning gift') in money or land to the woman herself, and she would have personal control over it to give away, sell or bequeath as she chose.

This of course all changed after the advent of the Norman Conquest in 1066, bringing with it the customs and laws of the Normans, and indeed there was great change in the rights and status of women. For those of high ranking birth especially, marriage was most often arranged by the woman's family or by the powerful, sometimes by the monarch himself, purely for political or personal gain, or in some cases as a reward to a favourite or for loyal services rendered. Women had a very limited share in feudal land owning, the husband owned everything, and Canon Law stated that no married woman could make a valid will without her husband's consent. Children were married at a young age, with the age of valid consent for girls being 12 years. Some young daughters were placed in an abbey and 'took the veil'. It was also fairly common for women to become nuns after the death of their husband. The only women with relative freedom to do what they wanted were rich widows. Some noble women were named heir to titles and estates, but it was still expected that a marriage would take place even for these women.

In fairness though, it would seem that this arrangement was sometimes just as distasteful to the husband, especially if he had no regard for the chosen woman.

Church and Daily Life:

Church and daily life were very closely tied together, and even the King was expected to attend chapel services. Indeed many Norman Keeps had a chapel, the best example of which is St John the Evangelist in White Tower, London.

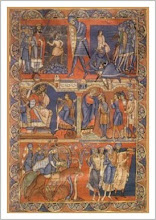

A Book of Hours, an illuminated book of prayers, texts, and psalms become the one of most common type of medieval illuminated manuscript. Some ladies of high ranking households also had a prie-dieu in their living quarters or solar. A prie-dieu (French: literally, "pray God") is a type of prayer desk mainly intended for private devotional use, but they can also often be found in churches of the European continent. It is a small ornamental wooden desk furnished with a sloping shelf for books, and a cushioned pad on which to kneel. Sometimes a prie-dieu consisted only of the sloped shelf for books without the kneeler, or instead of the sloping shelf a padded arm rest was provided.

Medieval Literature:

The Middle Ages saw the beginnings of a rebirth in literature. Early medieval books were painstakingly hand copied and illustrated by monks. Paper was a rarity, with vellum, made from calf's skin, and parchment, made from lamb's skin, were the media of choice for writing. Students learning to write used wooden tablets covered in green or black wax. Most books during this era were bound with plain wooden boards, or with simple tooled leather for more expensive volumes.

Language also saw further development during the Middle Ages. Capital and lowercase letters were developed with rules for each. Books were treasures and were rarely shown openly in a library, but rather kept safely under lock and key. Indeed, some people might have been tempted to rent out their books, while for others desperate for cash a book was a valuable item that could be pawned.

In addition, wandering scholars and poets travelling to the Crusades learned of new writing styles. Courtly Love spawned interest in romantic prose. Troubadours sang in medieval courtyards about epic battles involving Roland, Arthur, and Charlemagne.

Some Literary Works:

Anthology of Old English Poetry:

The Exeter Book, also known as the Codex Exoniensis, which dates to the tenth century, is an anthology of Anglo-Saxon poetry, and one of the four major Anglo-Saxon literature codices. It was donated to the library of Exeter Cathedral by Leofric, the first bishop of Exeter, and is the largest known collection of Old English literature that exists today. Proposed dates of authorship range from 960AD to 990AD. However, the Book's heritage becomes traceable around 1050 when Leofric was made Bishop at Exeter. Among the treasures which he is recorded to have bestowed upon the then impoverished monastery is one described as "mycel englisc boc be gehwilcum þingum on leoðwisan geworht" - that is: "a large English book of poetic works". This book has been widely assumed to be the Exeter Codex as it survives today.

A Link which includes further information and images of the text:

• The Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry

Romance Genre and the Song of Roland:

As a literary genre, romance or chivalric romance refers to a style of heroic prose and verse narrative current in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Romances often drew on the legends and fairy tales and traditional tales about Charlemagne and Roland or King Arthur.

The Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland) is the oldest remaining major work of French literature. It exists in various different manuscript versions, which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. The oldest of these versions is the one in the Oxford manuscript, which contains a text of some 4,004 lines (the number varies slightly in different modern editions) and is usually dated to the middle of the twelfth century, ie. between 1140 and 1170. The epic poem is the first and most outstanding example of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries and celebrated the legendary deeds of a hero.

• The Song of Roland

The Lais of Marie de France:

These are a series of twelve short narrative Breton lais written by the poet Marie de France in the late twelfth century. They are short, narrative poems that are notable for their celebration of love and in general focus on glorifying the concept of courtly love through the adventures of their main characters. Two of Marie's lais "Lanval" and "Chevrefoil" mention King Arthur and his Knights. Very little is known about Marie herself but it is thought she was born in France and wrote in England and was probably a contemporary of Chrétien de Troyes.

Harley 978, a thirteenth century manuscript housed in the British Library, preserves all twelve lais. The manuscript also includes a 56 line prologue in which Marie writes that she was inspired by the example of the ancient Greeks and Romans to create something that would be both entertaining and morally instructive, and she also states her desire to preserve for posterity the tales that she has heard.

• The Lais of Marie de France

Medieval Clothing and Jewellery:

The following links provide some very interesting information and images about medieval jewellery and clothing. They include information about the materials used, styles, and the social and economic value of jewellery items, as well as the garments worn by both men and women.

• Medieval Jewelry and Clothing.

• "Wool is the whole wealth of my people"

• Fashion - Saxon and Medieval

• Hullwebs - daily life, marriage, and family

• Anglo-Saxon Women 410AD to 1066

For women in particular, spinning and weaving, needlework and tapestry, and the preparation of 'Simples', homemade herbal remedies for various ailments, were common pursuits.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment